Semaine Issue 8,

Semaine

Pedagogue & Semiologist

Arno Stern is 99 years old. He surprises us with his presence and his lively eye, this hybrid appearance, somewhere between the wise and the young man. No doubt, he is a bit of both. The ethnologist and semiologist considers that no matter what, we remain forever the child we once were. He hates classifying people according to age and compartmentalizing his thinking. He does not, in truth, like any form of convention. It is this total freedom that has guided all of his work. Arno Stern is famous for having created Le Closlieu 70 years ago, a painting studio concept that made him famous, and which thousands of people from all over the world have experienced. The space itself is difficult to describe, as it tries to escape all the rules and all qualifications “No metaphor can fit.” laughs his 52-year old son, André. André, is an author and researcher continuing his father’s work by adding his own mark, his vision and new scientific approaches. Transmission between the Sterns is central. André speaks of a “duty to remember.”

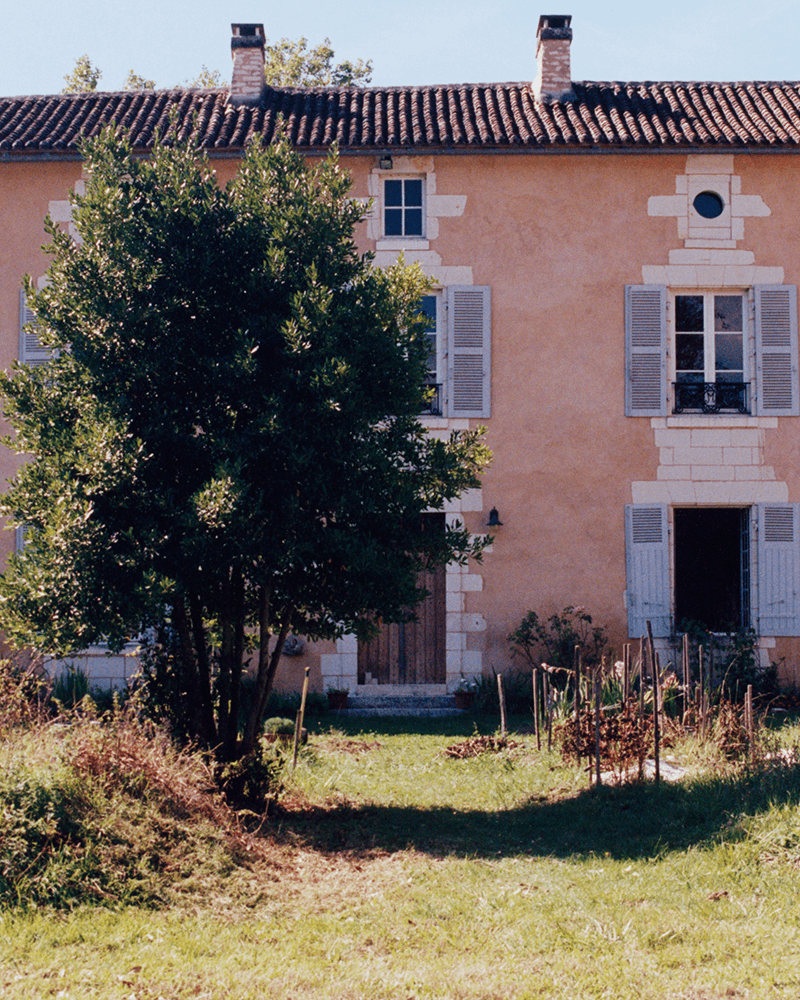

In their story of transmission, there is no issue of translation. He says, simply, “I have no problem of filiation; I am my father’s son”. All the Sterns live under the same roof, they don’t speak of “family” but of “constellation”, which sounds a bit like a new age community, but which looks more like a haven of peace. Arno and his wife Michèle, their children Eléonore and André, their partners and their grandchildren, opened the doors of this idyllic estate to our team and to the director Lubna Playoust, who has known Arno from the time she was his student, with her son, who was 6 years old at the time. Their warm welcome is an integral part of the poetry that emerges from the place.

At first glance, Le Closlieu is a bare workshop, closed and without windows, surrounded by high and colorful walls, filled with A1 sheets which gradually clump together. Eighteen pots of paint colors are available on a curious table, split in two, like a two-tiered bench, called “the palette table”. Groups of fifteen people enter it for an hour and a half. The assembly is mainly made up of children but there are also a few adults, who move back and forth between the table and the wall, in a dynamic that is as individual as it is collective.

Everyone applies themselves to their drawing, or rather their “trace” as Arno calls it, without restraining themselves and with the certainty that no one else will comment on it. No document will leave the Closlieu, thus protecting its authors from unwelcome regard the works are stored on site, protected from judgment. Michèle Stern also says that they bought the large house in which they live today to store the 500,000 archives. This is what distinguishes “Le jeu de peindre” (“The game of painting”), as he called it, from the conception of a work of art”.

Le Closlieu does not place the child in the process of an artist who must have a goal and establish communication with an audience. They stay in the pure act of creation and observation. They let go of all possible expectations and value judgments. It is a laying bare, a gentle but direct connection with the present moment which helps us return to the essence of what inhabits us and moves us. “People give vent to something special because they know there is no after. People’s motivations are the most varied, each one will leave the signs, the labels, the handicaps, the judgments, the discriminations at the door, to plunge into a new world.” Explains André.

To understand his approach to childhood, we must go back to his own. Born on June 23, 1924 in Kassel, Germany, the thinker came from a Jewish family. In 1933, he and his parents fled Nazi persecution. Arno remembers in the book of interviews with his son published at Marabout Editions: Poser sur nos enfants les yeux de la confi ance. “Putting the eyes of trust on our children”, the day when everything changed: he wanted to park his little red pedal car with which he was playing, when his mother called him. They had to leave. They got into a car, and never came back. They emigrated to France, where they experienced long years of wandering and poverty.

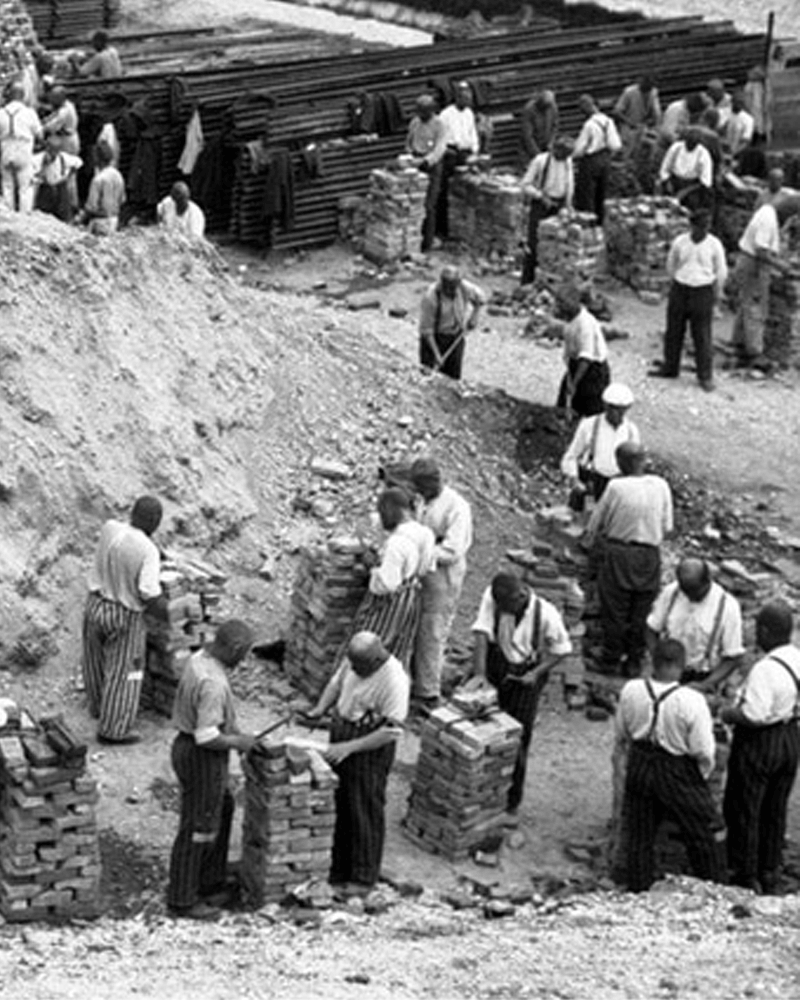

Threatened by Vichy authority, they escaped, but found themselves at the Swiss border. Arno spent his adolescence interned in a work camp. “Arno’s childhood is absolutely metaphorical and loaded with meaning.” explains his son André. “He lived twelve years in the middle of war, in the worst conditions imaginable: the escape, the threat of cannons, the need to hide in the straw when there was a German tank, under the red sky of bombings, and then there was hunger, fear, misery, this feeling of being nothing, and of being able to be denounced by friends or comrades at any time… There is nothing worse. And yet, when Arno is asked what his childhood was like, he says: it was wonderful.”

Arno’s childhood was great, he explained to his son, because he had the necessary “attachment.” He was in material precariousness but had a home base, an incredible safety net: the love of his family, and that was enough for his happiness.

Well before the advances we are familiar with today in child psychiatry, Arno advocated a completely unique approach. The era insisted on punishment and constraint as the main educational values, while Michèle and Arno decided to teach Eléonore and André themselves. They placed listening and respect at the center of education. “Since the 1950s Arno has been the initiator and pioneer of all of today’s thinking. This is why it takes its place alongside the sacred scholar of the field” adds his son.

Even if he doesn’t like to talk about “education” so much as “attitudes”. Like his father, he does not believe in ready-made recipes. “The idea is not to develop yet another method, but to give people enough information so that they can create their own systems, free, enlightened, in their own constellations.” Changing the rules of the world is within everyone’s reach. “To believe that freedom is the prerogative of a certain situation prevents you from allowing yourself to escape from it, and that is a victory for the system.” And to recall that his father built the foundation of his thinking, even though he had nothing.

The idea of the Le Closlieu was born by coincidence. At the end of the war, Arno and his family returned to France. Because of the political situation, he had been unable to study. At the age of 22, in 1946, he was hired in an orphanage in the suburbs of Paris. “Each educator proposed an activity: theater, piano. What he liked were colors, drawing, paper, his favorite activity, and he made the children paint. He didn’t intend to teach them anything, he just saw that it was an activity that the children carried out with enthusiasm because it was free. It was to keep them busy, to take care of them. And it was a wave…” says André. He then set up a similar workshop in St Germain des Prés in Paris which became famous under the name of “Académie du jeudi” (“Thursday Academy”) for 33 years, before being transferred in 1987 to Madeleine. He officiated his sessions, of late, in the 15th arrondissement of Paris.

At the beginning of his studies, Arno discovers, astonishingly, that the children all draw the same thing, like this popular house with a triangular roof, which does not really exist in Paris. Is it because all these children had the same education? he asks himself. To find out, in the 1960s, he decides to travel around the world. He travels the corners of the world, Afghanistan to Mauritania, to meet children who have never had access to drawing and observes what comes from their first drawings. Arno is soon surprised to always find the same codes, despite the disparities.

He deduces that we all have a memory that begins before we are two years old. “The “organic memory” he explains in the book of interviews with André, “memorised the events of our evolution, of our development.”

… for the full article, become a subscriber.

By Claire Touzard for Semaine.

Photography by Wendy Huynh.

Where three generations live and work together, harmoniously.

"Three generations who live and work there together, the property we're restoring, with its forest and fields, and which is home to all my work. In the forest, we have a place where my grandchildren, André and I go, almost every day, to taste, play and listen to music."

French Countryside,

France

"Where I survived war and Nazi persecution, discovered music and literature."

Affoltern,

Switzerland

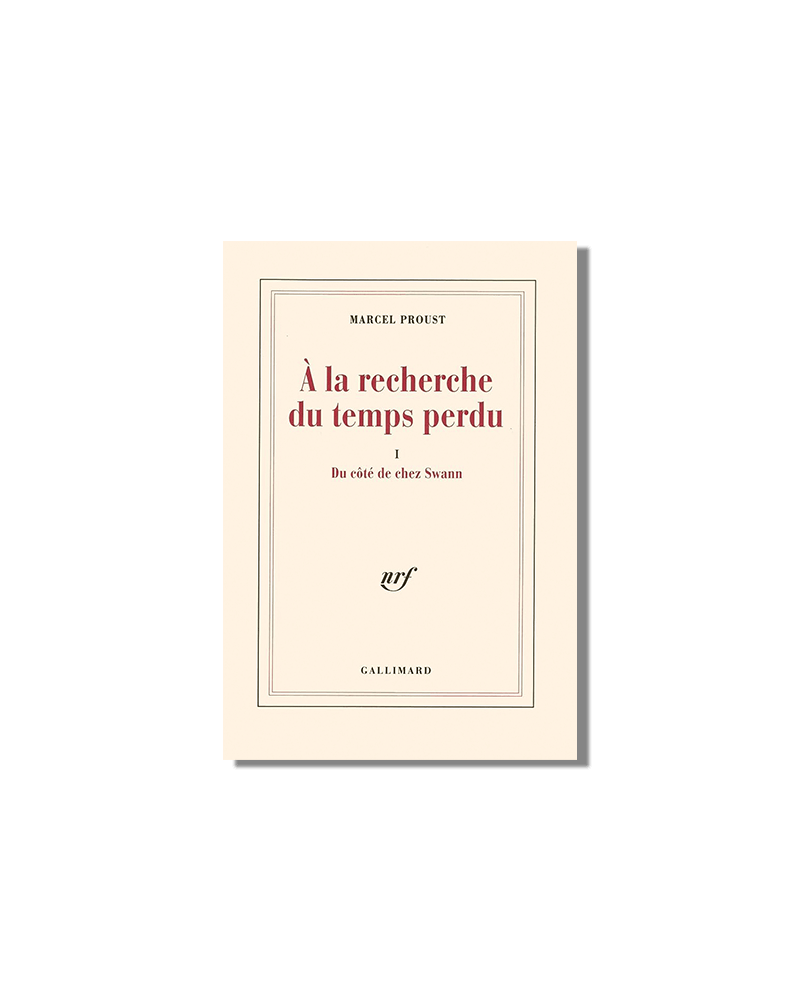

From Proust to Krishnamurti, see the world through Arno’s literary eyes.

£23

This novel follows the narrators memories of childhood and experiences into adulthood in high society France, between the late 19th to early 20th century.

Discover what Arno has been watching.

Become a member today to enjoy all our Tastemakers address recommendations on our interactive travel guide world map!

SUBSCRIBE NOWWhat does the word “taste” mean to you?

Arno:

To have a personal, original and rare aesthetic requirement.

Do you have a life motto that you live by?

Arno:

Children can do what they want, and want what they can.

What was the last thing that made you laugh?

Arno:

A funny line from Antonin, my eldest grandchild: “No matter how you pronounce German, there’s always a dialect in which it will be correct!”

What are your favourite qualities in a human being?

Arno:

Enthusiastic people. People with convictions and who are irreplaceable.

Who is your hero?

Arno:

My father, Isidore Stern.

What is your best quality?

Arno:

Being a freethinker.

What would your last meal on earth be?

Arno:

My Mother, or my wife Michèle’s, Apfel Schalet.

What does success mean to you?

Arno:

To answer that question. To pass on to my family and to humanity a work that changes the world. That my life has included encounters with particularly precious people.

If you had the power to change anything you wanted in the world, what would you change?

Arno:

Relationships with children.