Strappy Little Sun,

Semaine x Little Sun x Little Furniture Assemblage

The shimmering visions of Olafur Eliasson want to make you sane. Adrift in sound, or lost in colour, what Eliasson does with his fields of kaleidoscopic noise and geometry defy easy definition. As such, an Eliasson show has become a banner event. With each new one, Eliasson wants to push for change, to strip out the meaning of the sensory experience and encourage change from it. It’s art as a catalyst, as our cue. It’s also, Semaine gleaned in conversation with Olafur, all quite fun.

His impossible art conquers weather, mocks death, stares at the sun. It’s an ancient trope: in Seneca’s Letters From a Stoic, the Roman philosopher asks “Are you telling me not to investigate the natural world? Or the source of light (is it fire or something brighter)? Am I supposed not to inquire into this sort of thing?” That was 4BC, this is now. “I see art, and creativity, as a way of being embedded in the world”, says Olafur—and only an artist “embedded in the world” can make a life in visions that seem not of it.

Some artists change the way we see the world, which is one way of describing what Olafur means to do with his work in natural materials and experiences—work like his fog-engulfing 2003 Tate Modern Turbine Hall weather project, the Heavens-suspended 2016 Palace of Versailles waterfall, the 2020 steel, and glass cyranometer in the Hochjochferner glacier.

After all, to Olafur, “art is not a way of escaping from reality but a way of changing that reality.” In sharing his reality, the Danish-Icelandic artist has become a rock star, occupying a space very few do in the modern lexicon. His sensory experiences seem to create a sort of frequency; something the viewer can tune into or out of, and the extent to which they do so profoundly affecting them. The livewire sensations of his piece are designed, in part, to cajole and comfort: “This can help counteract the numbing effect that is caused by all of the news and information we are constantly exposed to.”

Light lacked in Olafur’s upbringing; it is now the crucible of his art. One memory stands out; visiting his grandparents in Iceland, amid the 1970s energy crisis, when blackouts were imposed: “When the lights would go off indoors, it would take a second for your eyes to adjust, and I remember this very particular experience of the light changing in quality as the long Icelandic dusk took over from the electrical lighting.” It’s now both medium and the message in his work, with Olafur’s convictions about light quality “the result of spending so much time in a part of the world where there are months of very little light”.

Now, well, let there be light. His clean energy non-profit organisation Little Sun is “very much about providing affordable, good quality lighting to people who do not have consistent access to electricity.” Little Sun works to create a thriving world powered by the sun, equipping farmers, students, health workers and refugees across Africa with renewable energy, and looking to artists to guide us all towards climate action. To date, the non-profit has provided power and light to over 3.2 million people who would not otherwise have access to it. Eliasson has described it with trademark wit as “a work of art that works in life.” This caption sits well with all that Eliasson touches. Olafur’s mission for Little Sun is, like the appeal of his art itself, democratic: “The quality and intensity of light affects everything we do – how we feel, how we sleep, how long we can work during the day and the quality of the work.” He and engineer friend Frederik Ottesen wanted to put power back in our hands: “While we were talking about this, the sun was coming down and we thought about prolonging the day by capturing the energy of the sun via a solar panel and then releasing it again through an LED light.”

Despite all this, Olafur has a striking modesty. The primary appeal of Olafur’s art is that it is democratic; you cannot help but have a reaction of the senses to his pieces, and as such, it is accessible to all. “The most profound sceptics I have met have changed their minds once they had a Little Sun in their hands”, Olafur attests. In his art too, there is no gestural pondering before a piece; you are in them, and they are around you. What other contemporary artist affords us this experience?

“In Real Life”, Eliasson’s 2019 show at the Tate Gallery, was a polyphonic weather system, a thirty-year retrospective, a meditation on climate change, and the gallery’s most-attended exhibit of the year. In these three decades, Eliasson has had three major concerns; nature, geometry, and an ongoing investigation into our perception of the two. The year before saw Olafur deposit melting blocks of ice, co-created with geologist Minik Rosing, outside the Tate Modern. Studio Olafur Eliasson crafts such spectacles, amassing premier “craftsmen and specialized technicians, architects, archivists and art historians, web and graphic designers, film-makers, cooks, and administrators”. Olafur has become known as a climate artist, saddled with the grim task of making us look up and pay attention to something, without adding to said thing’s problem.

Some artists veil the world to tell us about it, others expose it, Olafur mythologises it. His smoke and mirrors, such as they are, lend a fabled touch that softens any threat of didacticism; they are monuments of collective beauty, like the world itself. This optimism in his work scans in the frank way he talks about our future, the collective task we face: “Governments and corporations are made up of individuals too, and they ideally respond to concerns that are in the general culture. We too often approach problems in the world as if they are not made by us, as if reality were not malleable, but we are all part of larger systems.”

The elemental quality of his work, married with his devoted charitable efforts, show an artist firmly rooted in the now. If today’s youth are happy to interrogate the climate crisis and unequivocal in demanding change, Olafur is quick to acknowledge that his generation “has often been stuck with a view of the present and of the future that is defined by what came before, basically taking the future for granted as being more or less like the past and depending quite a bit on tradition. I have the sense that the children and young people of today are more attuned to the future, so that they view the present continually from the perspective of the future.”

His art gives us profound glimpses into the biggest problems we face—holding up a mirror to ourselves, allowing us to see our world in all its blazing, brilliant, brutal colours, and ask the question, perhaps, now, the only question there is to ask: “Isn’t this worth saving?” Olafur, for one, will continue looking for the light: “This is the perfect moment to think about how we can shape our future world now.”

By Jonathan Mahon-Heap for Semaine.

Photography by Tomas Gislason.

We’re exploring a bit differently this week. How? By entering virtual communities where can “go” to channel the inner optimist in all of us. Let’s go there together.

"Let's reach for the sun" and feel, change and engage with the impacts of solar energy. "Reach for the Sun: Ten Steps to Creating a Solar-Powered World" is a global creative communications campaign here to "help tackle climate change and end energy poverty, accelerating the transition to net-zero carbon emissions and universal access to clean, affordable energy."

Reach For the Sun Campaign,

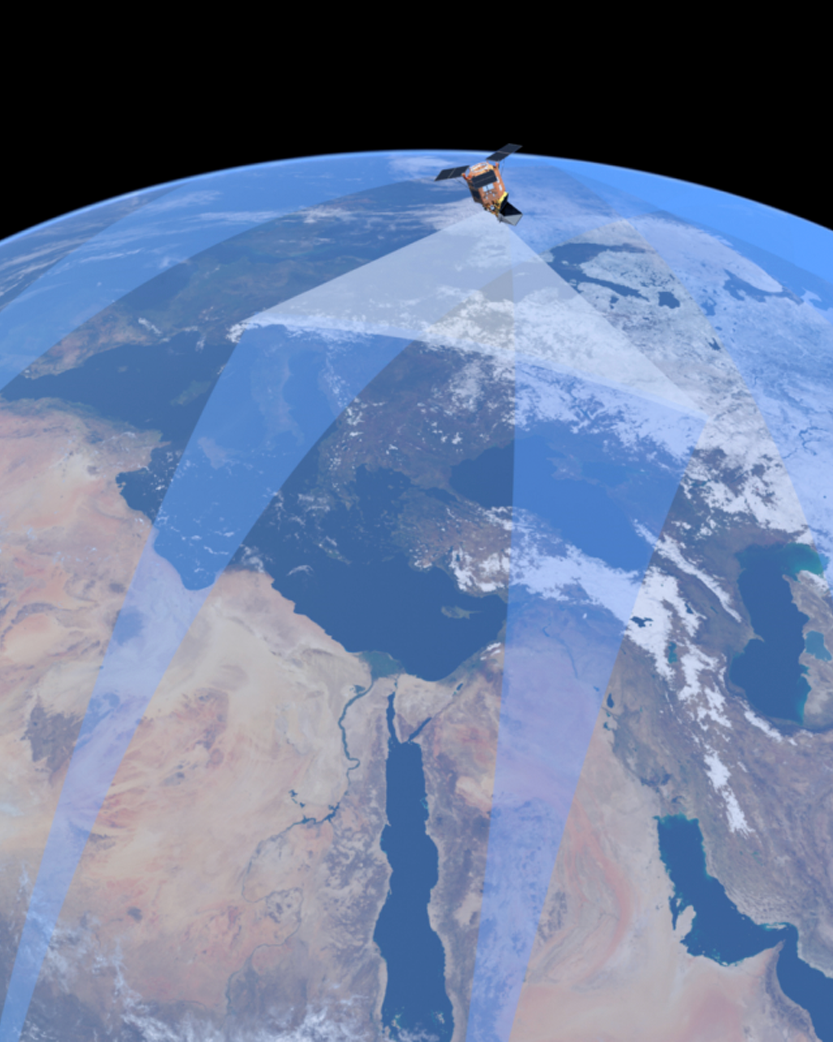

Explore the world of Earth Speakr, a profound piece of artwork that allows kids to amplify their messages regarding the climate.

Artwork by Olafur Eliasson,

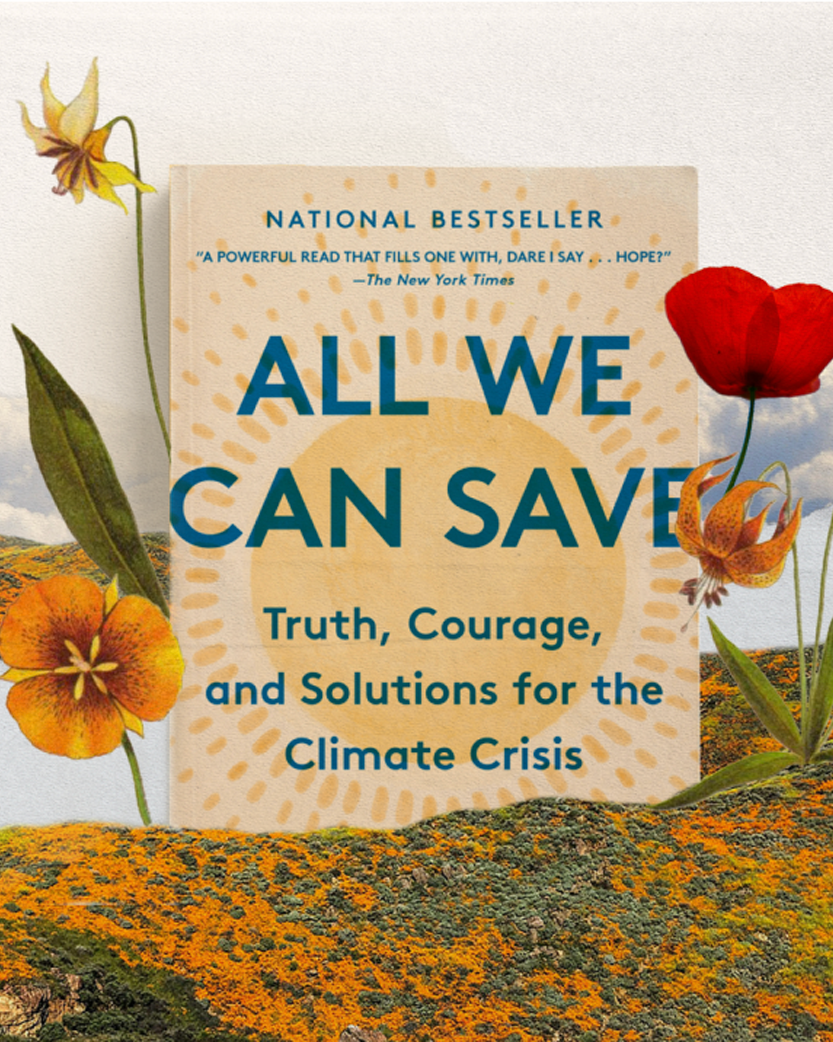

Explore this feminist climate renaissance, nurturing a welcoming, connected, and leaderful climate community, rooted in the work and wisdom of women.

A community fighting towards a better climate,

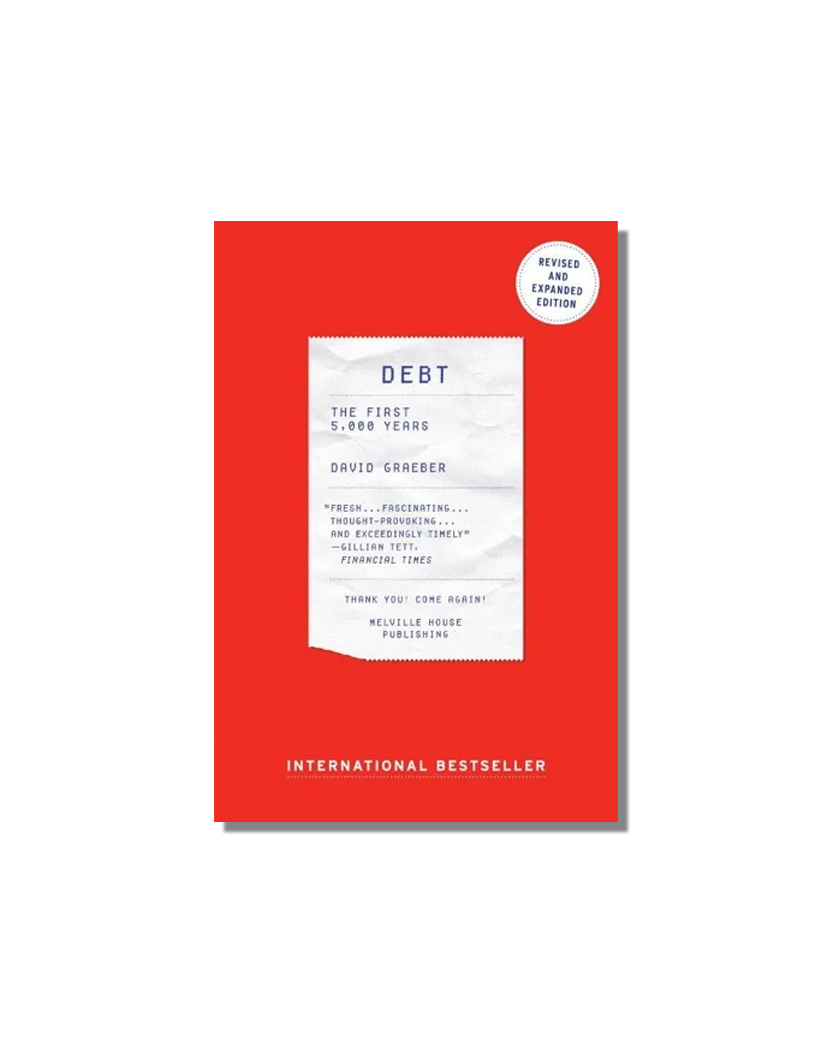

This week’s list of reading is extra long. We hope that this reading list, taken from Little Sun’s #reachforthesun campaign, will inform, inspire and incite action. We first need to understand the problem in order to fix it.

£18.99

Anthropologist David Graeber presents a stunning reversal of conventional wisdom: he shows that before there was money, there was debt and a society divided into debtors and creditors.

£3.99

Bringing you Greta in her own words, this book is a collection of her speeches on climate change, compiled into one rallying cry.

£9.99

A man-made problem with a feminist solution, Mary Robinson's profound manifesto argues for hope amongst the climate crisis.

£11.99

If you're curious about how large your carbon footprint might actually be, as well as ways to reduce it, this book is the one for you.

£10.99

What has nature ever done for us? Some good, some bad but most importantly they have had a profound impact on the way we live, in the pas, present and future.

£15.99

Liquid life, a fluidity that is subject to change in the most precarious of manners and a reflection of a modern society that fails to garner certainty.

From a mindful meditation exercise helping you reconnect the power of the sun, to a TED talk that shows how to get the United States off of coal by 2050, you don’t want to miss this.

Energy innovator Amory Lovins shows how to get the US off oil and coal by 2050, $5 trillion cheaper, with no Act of Congress, led by business for profit.

You're not the only one feeling overwhelmed by climate change. Sign up to this newsletter to find reasons for hope in new science and technology delivered every Thursday.

Solnit celebrates the unpredictable and incalculable events that so often redeem our lives, both solitary and public. Searching for hidden stories after disasters like post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans.

Conceptualised by Studio Olafur Eliasson (SOE) and Interacting Minds Centre (IMC), #WeUsedTo was launched in May 2020 as a tool to explore how the Covid-19 pandemic disrupts lives around the world, by prompting reflections about our past and present realities. Primarily made up of online responses, you too can add your reflection on the way the pandemic has changed your past and present.

Become a member today to enjoy all our Tastemakers address recommendations on our interactive travel guide world map!

SUBSCRIBE NOWWhat makes you want to create?

Olafur:

I see art, and creativity, as a way of being embedded in the world, of affecting my surroundings directly and the society in which I live. It is not a way of escaping from reality but a way of changing that reality. Art is engaged on a day to day level with touching and moving people, offering them direct experiences of things they may only have seen or heard from a distance. This can help counteract the numbing effect that is caused by all of the news and information we are constantly exposed to.

We can’t help but observe that in Scandinavia there is a particular relationship to light or lack of, we should say. Do you find this unique relationship with light has influenced your work?

Olafur:

Yes, very much so. One experience in particular stands out for me. As a child, I would visit my grandparents in Iceland. At the time, during the energy crisis of the 1970s, there were blackouts in the evenings that were imposed to conserve electricity. As it was during the summer, when the sun rarely sets in Iceland, it was often still light outside, if only dimly. When the lights would go off indoors, it would take a second for your eyes to adjust, and I remember this very particular experience of the light changing in quality as the long Icelandic dusk took over from the electrical lighting.

The quality and intensity of light affects everything we do – how we feel, how we sleep, how long we can work during the day and the quality of the work. And this conviction about the importance of light quality, which I have as a result of spending so much time in a part of the world where there are months of very little light, has influenced my desire to work on projects that deal with light and also my decision to create a solar light like Little Sun, which is very much about providing affordable, good quality lighting to people who do not have consistent access to electricity.

What have been the most unexpected results, learnings and observations gleaned from Little Sun and tell us a little bit more about what created the impetus to start this wonderful project that we’re delighted to collaborate with!

Olafur:

A few years ago, my friend Frederik Ottesen, who is an engineer, was working on a solar plane, and I was helping him with some questions regarding its design. We were discussing ideas around and we came up with the idea that everyone in the world should be able to hold a bit of sunlight in the palm of the hand. We were asking ourselves: How does it feel to have energy, to have power? While we were talking about this, the sun was coming down and we thought about prolonging the day by capturing the energy of the sun via a solar panel and then releasing it again through an LED light. This is how Little Sun was brought to the world. With the solar lamp, I take the energy from the sun, which belongs to all of us, and take it with me. I am happy to see this simple idea has now become a universal project, bringing solar energy to regions where electricity is still a luxury, as well are raising the global consciousness about the climate crisis.

When we started working on Little Sun, Frederik and I travelled to Ethiopia to develop the design of the solar lamps. While we were talking to people, we found out that everyone wants beauty in their lives. Initially, the design was quite practical. We have realised it mattered to create a desirable, creative object that inspires people worldwide. This is why we have decided to create objects that are perceived as beautiful, no matter if you live in a small village in Ethiopia, or in a European city. I believe the intersection between aesthetics and high technical standards is what makes the solar lamps innovative. The most profound sceptics I have met have changed their minds once they had a Little Sun in their hands. Taxi drivers in Addis Ababa have even become Little Sun ambassadors by testing it and seeing the impact it has on their families.

To what extent does the growth of individual eco-consciousness matter in a world where corporate and government consciousness is so slow to respond?

Olafur:

Governments and corporations are made up of individuals too, and they ideally respond to concerns that are in the general culture. We too often approach problems in the world as if they are not made by us, as if reality were not malleable, but we are all part of larger systems. Our individual actions need to be viewed in this context – they matter, but mostly in as much as they contribute to the systems and can drive others to act as well. Governments and the international community, need to act now, but it is clear that in order to meet the challenge of the climate crisis, we all need to be active in our own fields and at all possible levels. But I am an optimist, and I would argue that we have more ability to change reality than we commonly realise.

What is the first thing someone should personally do in their day-to-day to reduce their output; either their energy emissions, or their plastic consumption, or both?

Olafur:

At a systemic level, we can organize and put pressure on politicians and governments. We can join others in calling on businesses and institutions to divest from fossil fuels and instead invest in sustainable energy and innovation.

In our lives, we can fly less and check to make sure our refrigerators, freezers, and air conditioners don’t use refrigerants called HFCs (hydrofluorocarbons), which are highly damaging to the climate. We can reduce food waste, adopt a plant-based diet, and buy products that leave little mark on the planet. If businesses see that this is where the money is going, they will follow.

We absolutely love what you have done with Earthspeakr! Today’s youth seem keen to interrogate their place in society and are unequivocal about the need for change; where does this confidence in opinion stem from, and how do you think they will respond to the unique challenges they face?

Olafur:

My generation has often been stuck with a view of the present and of the future that is defined by what came before, basically taking the future for granted as being more or less like the past and depending quite a bit on tradition. I have the sense that the children and young people of today are more attuned to the future, so that they view the present continually from the perspective of the future. I see this not only in their awareness of the potential affects on our future climate, in movements like Fridays for Future and Extinction Rebellion, but also in the long-overdue reassessment of the monuments and statues that solidify the past in our public spaces. This is the perfect moment to think about how we can shape our future world now.